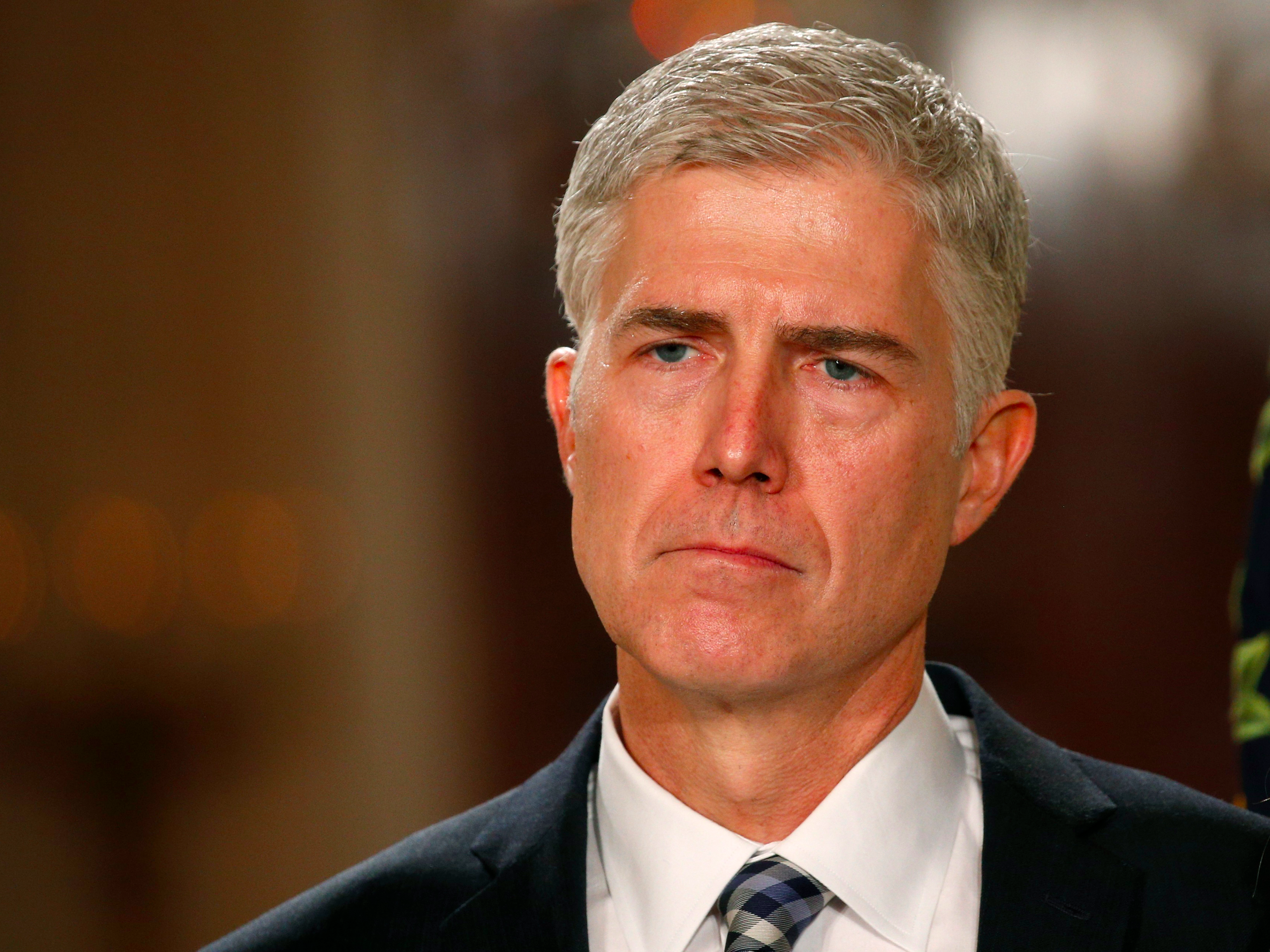

As Democrats intensify their criticisms of Supreme Court nominee Neil Gorsuch, whose confirmation hearing is scheduled for Monday, his track record on criminal cases has become a focus.

Despite Gorsuch’s staunch conservative credentials, his history on criminal law is more difficult to pigeonhole. He has ruled in favor of both criminal suspects and police officers on a variety of issues, from excessive force to privacy cases.

Gorsuch, who serves on the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals in Denver, has previously indicated he thinks there are too many federal criminal laws and regulations bogging down the courts.

In a 2013 speech, he criticized the growing number of criminal offenses and regulations have become increasingly difficult to keep up with:

"Without written laws, we lack fair notice of the rules we must obey. But with too many written laws, don't we invite a new kind of fair notice problem? And what happens to individual freedom and equality - and to our very conception of law itself - when the criminal code comes to cover so many facets of daily life that prosecutors can almost choose their targets with impunity?"

Gorsuch has received praise from defense lawyers and other legal experts for often intrepreting laws in favor of defendants, a tendency similar to that of the late Justice Antonin Scalia. Scalia was known for erring on the side of even the most unpopular suspects (he once referred to himself as "the darling of the criminal defense bar").

Other criminal-justice-reform advocates have remained wary. People for the American Way, a liberal advocacy organization, called many of Gorsuch's criminal-justice rulings "troubling," arguing that several of his dissents that favored defendants had been unique. Gorsuch more often dissented against rulings that "vindicated important constitutional rights," the organization said.

Here are some of the most interesting cases Gorsuch has ruled on:

Gorsuch has ruled in favor of defendants in excessive force cases

In a 2016 opinion on excessive force, Gorsuch broke with his colleagues on a case involving a 13-year-old who had been arrested, handcuffed, and sent to juvenile detention after making burping noises in class.

When the judges ruled that the school officer's actions were protected under qualified immunity, which shields public officials from liability for civil damages, Gorsuch issued a colorful dissent arguing that the student should have been able to sue the officer for using excessive force.

"If a seventh grader starts trading fake burps for laughs in gym class, what's a teacher to do? Order extra laps? Detention? A trip to the principal's office? Maybe. But then again, maybe that's too old school. Maybe today you call a police officer. And maybe today the officer decides that, instead of just escorting the now compliant 13-year-old to the principal's office, an arrest would be a better idea," Gorsuch's dissent began.

Gorsuch then argued that other courts have refused to hold children criminally liable for small-scale "antics" that merely created disruptions within classrooms, and reserved criminal convictions for those who perpetrate more substantial offenses that affected entire schools. Gorsuch said a distinction must be drawn "between childish pranks and more seriously disruptive behaviors."

The dissent has become one of Gorsuch's most often-cited criminal law opinions, vividly demonstrating his reluctance to broadly apply criminal laws where no criminal intent can be found.

Gorsuch did, however, praise the judges he disagreed with for interpreting the statute as they understood it to be written, even quoting Charles Dickens in describing the law as "a ass - a idiot."

As a textualist largely in the mold of late Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia, Gorsuch has frequently advocated for interpreting laws based solely on text, regardless of the desirability of the outcomes.

"I admire my colleagues today, for no doubt they reach a result they dislike but believe the law demands - and in that I see the best of our profession and much to admire. It's only that, in this particular case, I don't believe the law happens to be quite as much of a ass as they do. I respectfully dissent," he wrote.

He has also ruled in favor of police and law enforcement in excessive force cases

While Gorsuch has come down against excessive force in some cases, including that of the 13-year-old, he has also ruled several times in favor of police.

In 2013, he argued that a police officer had not used excessive force when he shot a fleeing suspect in the head with a Taser.

The officer had been questioning 22-year-old Ryan Wilson on whether he was illegally growing marijuana, when Wilson gave chase. He died after being struck by one of the Taser's prongs.

"The situation at the time the officer fired his Taser was, thus, replete with uncertainty and a reasonable officer in his shoes could have worried he faced imminent danger from a lethal weapon," Gorsuch wrote in the majority opinion.

"We sympathize with the Wilsons over their terrible loss. But the Supreme Court has directed the lower federal courts to apply qualified immunity broadly, to protect from civil liability for damages all officers except 'the plainly incompetent or those who knowingly violate the law.'"

In her dissent, his colleague Judge Mary Beck Briscoe argued that the officer had been warned during his training not to aim the stun gun at a person's head or throat unless necessary.

Gorsuch once argued fiercely against using a prior ruling to uphold a man's firearm conviction

In a 2012 case, Gorsuch vehemently urged his colleagues to review a prior ruling that was cited as precedent in upholding a defendant's firearm conviction.

The defendant, Miguel Games-Perez, was prosecuted for "knowingly violating" a statute prohibiting a convicted felon from possessing a firearm in interstate commerce.

Gorsuch took exception to the 10th Circuit's ruling denying Games-Perez's petition for an appeal, arguing that prosecutors had only been able to prove Games-Perez knew he was possessing a firearm - not that he knew he was a convicted felon while he possessed the firearm.

Gorsuch said the issue was largely one of grammar and linguistics, arguing the word "knowing" should apply to each element of the crime. It's a significant distinction, Gorsuch argued, particularly because a prior judge had mistakenly given Games-Perez reason to doubt he was a felon.

"People sit in prison because our circuit's case law allows the government to put them there without proving a statutorily specified element of the charged crime," Gorsuch wrote in his dissent.

"This court's failure to hold the government to its congressionally specified burden of proof means Mr. Games-Perez might very well be wrongfully imprisoned."

He even diagrammed a sentence to show why a defendant should be given fewer charges after fatally shooting someone

Gorsuch's commitments to interpreting the law as "the words on the paper say" and not over-criminalizing innocent conduct were on full display in a 2015 decision in which he used "plain old grade school grammar" to determine the legal penalties imposed on defendants accused of using a firearm "during and in relation to any crime of violence of drug trafficking crime."

Gorsuch was ruling on a case in which prosecutors were attempting to charge a defendant, Philbert Rentz, with two violations for allegedly firing a gun once. Prosecutors argued that since a single shot hit and injured one person, then struck and killed another, two separate "crimes of violence" had been committed and should be penalized accordingly.

Gorsuch disagreed, saying prosecutors must look to the statute's verbs for their accurate meaning, which he argued only supported one count of using a firearm during a crime of violence.

"It's not unreasonable to think that Congress used the English language according to its conventions," he wrote, before proceeding to explain each verb in the statute and how the adverbial prepositional phrases modify them.

"Just as you can't throw more touchdowns during the fourth quarter than the total number of times you have thrown a touchdown, you cannot use a firearm during and in relation to crimes of violence more than the total number of times you have used a firearm."

Gorsuch has also come to the defense of people who say police violated the Fourth Amendment and conducted illegal searches

Gorsuch is seen as somewhat of a moderate when it comes to illegal searches, often siding with those who say they were the subject of unconstitutional searches by police.

Although he has ruled in several cases in favor of police accused of conducting illegal searches, he is best known for his opinions siding with defendants.

In one majority opinion last year, Gorsuch cited the Fourth Amendment in overturning a man's conviction of possessing and sending child pornography. The man's emails containing the images as attachments had been opened without a warrant, after AOL's system detected the file and sent it to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC) through its CyberTipline.

"There can be no doubt that NCMEC does important work and that its work can continue without interruption … We are confident that NCMEC's law enforcement partners will struggle not at all to obtain warrants to open emails when the facts in hand suggest, as they surely did here, that a crime against a child has taken place," Gorsuch wrote.

His opinions on the Fourth Amendment show he is "not a knee-jerk vote for the government," George Washington University law professor Orin Kerr told the New York Times last month.

Gorsuch once wrote a dissent in which he sided with the defendant and put up a staunch defense of private property rights. In the 2016 case, police had knocked on a homeowner's door despite "no trespassing" signs on the property - a move Gorsuch said should have been done with a warrant.

"If clearly posted No Trespassing signs can revoke the right of officers to enter a home's curtilage their job of ferreting out crime will become marginally more difficult," Gorsuch wrote.

"But obedience to the Fourth Amendment always bears that cost and surely brings with it other benefits."